Semiotics: public language (Northern Ireland); the printed word (newspapers)

By Colman Cassidy

Introduction

Semiotics is the construction of worlds of meaning. It sees communication as the production and exchange of meanings: how messages and texts interact with people to produce meanings. The message, then, is a construction of signs, which through interaction with the receivers, produce meaning. 1)Fiske, John, Introduction to Communication Studies. London: Routledge, 1990, pp.2-5. Once the message is transmitted, the sender – defined as transmitter of the message – declines in importance. The emphasis now shifts to the text and how it is read.

Semiotics is the construction of worlds of meaning. It sees communication as the production and exchange of meanings: how messages and texts interact with people to produce meanings. The message, then, is a construction of signs, which through interaction with the receivers, produce meaning. 1)Fiske, John, Introduction to Communication Studies. London: Routledge, 1990, pp.2-5. Once the message is transmitted, the sender – defined as transmitter of the message – declines in importance. The emphasis now shifts to the text and how it is read.

The sign is the fundamental construct of semiotics, which the philosopher, C.S. Peirce (1931-58) – regarded as the founder of the American tradition of semiotics – defines simply as: “Something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. It addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more developed sign. The sign which it creates I call the interpretant of the first sign. The sign stands for something, its object .” 2)Zeman, J., “Peirce’s theory of signs”, in T. Sebeok, (ed.), A perfusion of sign. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977, pp.22-39.

For Peirce’s European counterpart, the Swiss linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure, the sign is a physical object with a meaning – comprising a signifier and its associated mental concept, the signified. The signifier is the sign’s image as we perceive it; the signified is the mental concept to which it refers.3)Fiske, pp.43-44

This essay takes meaning as its overriding theme. It sets out to explore meaning in the context of two main sub-constructs, Northern Ireland and the printed media. Part I focuses on the public language of Northern Ireland and explores recent development in the arts there (with reference to a symposium on 6 December 1991 in the National Gallery of Ireland) as a metonym for the problems – social and cultural – that have overtaken the beleaguered province.

Part II explores media coverage of Chernobyl in the light of Kaufmann and Broms’s Semiotica article (1988) and attempts to provide a more pragmatic appraisal a posteriori through additional information and the use of Croghan’s “Theory of Meaning”. In conclusion, the essay briefly combines the two sub-constructs, to highlight the hidden constraints that journalists in the Republic’s printed national media can face in probing the cultural quagmire that currently exists in Northern Ireland.

Part I: Crumbling Walls

- Two poetic conservatives

- In the city of guns and long knives

- Our ears receiving then and there

- The steriophonic nightmare

- Of the Shankill and the Falls

- Our matches struck on crumbling walls

- To light us as we moved at last

- Through the back alleys of Belfast.

Michael Longley: dedicated to his fellow Ulster poet, Derek Mahon. 4)Quoted by Liam Kelly, president of the Association International des Critiques d’Art (Irish Section) from his review of art in Northern Ireland, 1992 – delivered to The City as Art symposium in the National Gallery of Ireland on 6 December 1991. The symposium was sponsored by the Association as a contribution towards Dublin’s year as European City of Culture.

The latter-day flaneur or busy city-dweller encounters a vast mosaic of signs that exist in chaotic, even random juxtaposition to each other, bombarding him with a continuous visual “noise” that homes in through a multiplicity of channels. He is forced to filter out and narrow down the number of channels through which he is being made aware – and must order his priorities relative to this sign bombardment at any one moment – past, present or future. Nonetheless, the entropic pull towards a breakdown in this self-ordering process is always real.

At a recent symposium on The City as Art in Dublin’s National Gallery, London art critic, Steve Willats spoke of the “secret language” of the city and made the point: “Contemporary life exists within a jungle of visual signs and messages that are vying with each other to influence our future thoughts and actions.” 5)cf. footnote (1); quote from Willat’s paper, Secret Language, read to the symposium.

One’s whole cultural experience, he claimed, is at some point mediated in this way – our engagement with culture being a constant process of decoding what has been encoded and life-positioned by someone else. The proliferation of signs that tell us what to do or who we are, are largely an unannounced feature of modern urban life: “A feature of this quietly spreading network of institutionally originated signs is their inherent reductiveness in the basic representation of complex reality. This simplification of complexity in signs towards universal, basic object, reinforces an authoritatively-made distancing between people, between those persons that originated a sign and those that receive its message.” 6)Ibid.

Such institutional signs are a “secret language” articulated somewhere out of reach of those to be affected, by corporations (including brand advertising) administrations and officialdom, which can inhibit the free expression of individual self-identity and creativity, Willats claims. Cities such as Belfast, Derry, (Palestinian) Jerusalem and Johannesburg are good examples. Significantly, too, there is a second secret language, in sign systems that manifest the self-identity, the community and the creative power of the sign-maker – presenting either as burnt out cars in jobless Finglas, wall murals, crumbling walls or stereophonic nightmare in war-torn Belfast – or wherever. It is articulated from highly personal expressions made public by people that are under pressure from the anonymity, passivity or even cultural alienation implied in the various institutional signs – and who state their opposition to its inherent determinism.

This second secret language is “subversive”, often consisting of spontaneous layerings made directly onto the very physical surfaces that radiate messages of institutional determinism. Such informal sign systems exist under cover as a counter-consciousness that has been marginalised from the very normality projected by society: “jumping out from behind its fabric to demand attention.” 7)Ibid.

Its effect? The pull towards chaos is continually held in check, Willats argues, until a sign of counter-consciousness intervenes: by switching attention to the secret language of counter-consciousness, the city-dweller becomes sensitised to the interplay between signs and their culturally repressed, yet more complex worlds of community meaning.

In a city such as Belfast – or Beirut – words, as semiotic symbols, are painted on walls only to be dispossessed and answered on other walls – in other words. Words interrogate the wall: they interrogate themselves into its structure like shades. In mid-1991, two young Scottish artists, Roddy Buchanan and Douglas Gordon brought ARMY – a large wall piece, consisting of bright red lettering scannerchromed onto canvas – to Northern Ireland. The work, appropriated from a gable wall in Glasgow, looked out on the streets of North Belfast from the Orpheus Gallery in York Street, where it visually body-checked citizens and passers-by for opinions, acceptances and rejections. “Where you stood was how you perceived it – Salvation Army to some, army of transgression to others,” says University of Ulster lecturer, Liam Kelly, the Gallery’s director. It has always been thought paradoxical that soldiers on patrol in Belfast wear uniforms designed to be effective camouflage in a rural landscape. The text, ARMY, finds no hiding place on the wall.

In a city such as Belfast – or Beirut – words, as semiotic symbols, are painted on walls only to be dispossessed and answered on other walls – in other words. Words interrogate the wall: they interrogate themselves into its structure like shades. In mid-1991, two young Scottish artists, Roddy Buchanan and Douglas Gordon brought ARMY – a large wall piece, consisting of bright red lettering scannerchromed onto canvas – to Northern Ireland. The work, appropriated from a gable wall in Glasgow, looked out on the streets of North Belfast from the Orpheus Gallery in York Street, where it visually body-checked citizens and passers-by for opinions, acceptances and rejections. “Where you stood was how you perceived it – Salvation Army to some, army of transgression to others,” says University of Ulster lecturer, Liam Kelly, the Gallery’s director. It has always been thought paradoxical that soldiers on patrol in Belfast wear uniforms designed to be effective camouflage in a rural landscape. The text, ARMY, finds no hiding place on the wall.

“The soft lyrical focus of the close reading, both optically and metaphorically, hardens to a street reality from a distance. ARMY’s meaning is ambiguous and confrontational. You cannot ignore it. It may affect you at some time, wherever you go.” 8)Kelly, op. cit.

The word, “Army”, used in this way has a metonymical quality that for some will simply be a shorthand for 300 years of cultural, religious and economic repression dating from the Battle of the Boyne; for others, perhaps subliminally, it will denote less Salvation Army than British imperialism at its most efficacious as an antidote to the Provisional IRA – a sense of security. By choosing ARMY as a part of this or that commmunity’s worldview to represent their entire reality – whichever – the susceptibilities of both sides are instantly pandered to in this stark four-letter signifier.

More recently, artists Philip Napier and Michael Minnis collaborated in a work entitled Governors for the Belfast 1991 exhibition, “Shifting Ground”, which explored the city as a power source in a traditionally protestant and male dominated culture. It consisted of revolving metal balls used in the linen industry as regulating mechanisms in working machinery, together with large photographs of former city fathers taken from statues around Belfast’s City Hall. It is interesting to reflect on the paucity of (non-religious) statues depicting individual women, apart perhaps from the ubiquitous Queen Victoria, whose statues, are in any event construed as signifiers to the signified (in an arbitrary sense) in much the same way as ARMY is, on both sides of the cultural divide. [The depiction of females in public language sculpture, almost inevitably focuses on the abstract; for example the gargantuan figure of Mother Russia in Volgograd (Stalingrad) – her sword alone is 12 metres long – as an eternal memorial to the 20 million Soviet citizens killed in the Patriotic War (World War II). Thematically, women are subsumed under this genre as the property of men – as wives, mothers, lovers; and as a rallying point for wartime recruitment lest this property be violated by the enemy.]

The Belfast artists, Napier and Minnis said of their installation that it was an attempt to articulate the language of the city: “That colonial, protestant male dominated ethic is always to the fore and it just seeps into you.” Their work may be seen as a valediction to the linen industry – once the staple industry of Ulster: women worked the machines and the governors, the men – albeit bourgeois men – were in control. In the exhibition catalogue the artists state: “The work ethic preaches the godliness of work and the sin of sloth. It is part of the code by which our lives are regulated. The authority of this cramped imperial logic is everywhere – in the public sculpture and the architecture of the city. Our lives, which surround these structures, are gradually challenging those codes.” 9)Kelly, op.cit.

The war-torn North has provided physical environments as public language that have been explored more by appropriate installation works than free standing sculpture: barriers, defensive architecture and surveillance towers, not forgetting the ubiquitous helicopter. Tony Hill, in an ambitious installation of baths first shown in Belfast and later, in a more extended form at the Project Gallery in Dublin, managed to combine references to the Long Kesh Dirty Protest, plumbing, stairwells, and security barriers with notions of the visual properties of structure and water – related to man as an index of measurement. Hill’s work is about language, structure and surface and is quietly rhetorical. For example, as part of a group exhibition, “Poesis, Line Object”, last year, he installed two screens made from discarded domestic doors – painted in limewash pigment and disposed by necessity to create a rigid geometry. The screens, titled Crown and Castle, are “anthropocentric”; in Hill’s work man is continuously measured by physical structures: they invite the viewer to be included/excluded – screening for what Kelly calls “a kind of colonial outreach”.

Part II: Print Media

“Newspapers represent one kind of public literature in which to look at a country’s collective unconscious and uncover some of the public myths – myths which structure and are structured by a country’s dominant signifying practice.” 10)Kaufmann, R., and Broms, H., “A semiotic analysis of the newspaper coverage of Chernobyl in the United States, the Soviet Union and Finland.’ Semiotica, 1988, 70, 1/2, pp.27-48.

Newspaper coverage of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster provided Kaufmann and Broms with an ideal opportunity to analyse the signifying practices of the United States, the Soviet Union and Finland. The ways in which information passes through a society are the key to that society’s culture. 11)Smith, Anthony, The Geopolitics of Information: How Western Culture Dominates the World. London: Faber and Faber, 1980, p.151.

The article describes how a semiotic grammar of the mythical level and signifying practices, designed by Greimas, was used to analyse newspaper coverage of Chernobyl in the USA, the USSR and Finland. In the Greimasan model, the grammar is composed of six actants through which the mythical level is explained: Subject, Object, Sender, Receiver, Helper and Adversary. The following grid represents a summary of their findings based on an analysis of the news coverage by the US-owned International Herald Tribune, Soviet Moscow News and the Finnish Helsingin Sanomat in the immediate aftermath of the Chernobyl tragedy. For example, the grid (below), adapted from the article’s Appendix, represents a taxonomic shorthand focusing on the six actants to facilitate the analysis of news coverage in the three papers from “a period of non-knowledge” in the days that followed the disaster, until several weeks afterwards.

The key actant was the Sender (journalistic standards), represented less by the individual reporter than the presentation of his copy in the paper. It is a salient point, as will be shown later. Significantly, much is made of the fact that in the case of the Moscow News, (owned by the Soviet government) the Sender as actant would not measure up to the investigative standards set by American journalism, as by implication denoted by “free enterprise”. Such a priori assumptions scarcely do justice to what in general, is a workmanlike article that could, however, benefit from some useful a posteriori fine tuning.

The key actant was the Sender (journalistic standards), represented less by the individual reporter than the presentation of his copy in the paper. It is a salient point, as will be shown later. Significantly, much is made of the fact that in the case of the Moscow News, (owned by the Soviet government) the Sender as actant would not measure up to the investigative standards set by American journalism, as by implication denoted by “free enterprise”. Such a priori assumptions scarcely do justice to what in general, is a workmanlike article that could, however, benefit from some useful a posteriori fine tuning.

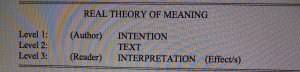

The Finns, too, are credited with mixed motives in their earlier attempts to play down the impact. Here too, the prima facie case can hardly be regarded as conclusive, given historical and in particular, economic ties between the Finland and the USSR since World War II. The wishful thinking displayed by Helsingin Sanomat in representing Chernobyl as a “manageable” disaster may have less to do with “creative” reporting (or even withholding information) than a genuinely held reluctance to disclose full details of the impact of the disaster to a vulnerable Finnish population in the absence of incontrovertible empirical evidence. To use a simple metaphor: living over a butcher-shop makes one contemplate one’s susceptibilities. One might suggest, too, that to a non-American, the unassailable image propounded in the article as the norm for US investigative journalism, sounds somewhat chauvinistic, naïve even – despite the best efforts of Woodruff, Bernstein et alia and could bear further analysis based on the Croghan (1986) “Theory of Meaning” model.12)Croghan, M.J., Where did Limbo go? The analysis of a Real Theory of Meaning. NIHE Dublin, 1986.

A “footnote” to the Chernobyl study concerning the experience of an individual American, Dr. Robert Gale, is worth appending and is indeed essential for a fuller analysis of current newspaper coverage of Chernobyl at the time, based on this model of meaning – using the Semiotica article as a starting-point.

[The writer was in Moscow on 7 June 1986, the day that Dr. Gale, head of the Bone Marrow Transplant Unit at the UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, held a press conference to announce details of a joint study on the medical consequences of Chernobyl.]13)Cassidy, Colman Sunday Press, Dublin, 3 August 1986.

Agreement for the joint study was signed by Gale, as chairman of the advisory committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry and Andrew Vorobiev, head of the department of haematology at a Moscow’s Central Institute for Advanced Medical Studies. It encompassed the long-term evaluation and provision of medical care for some 135,000 people evacuated from the danger zone surrounding the worst nuclear disaster in recorded history. They will have to be closely monitored for the rest of their lives.

Gale’s book, Chernobyl: The Final Warning (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1988), relates how he – an American Jew – acting as a private individual, and not representing his government, was in the unique position to hold such a press conference: he had heard on the radio the news of the nuclear holocaust in Ukraine. He knew that the Soviets would not accept medical help from the American government. He also knew that he and his colleagues had state-of-the-art skills and ready access to transplant registry files which could pinpoint suitable donors for bone marrow transplants at the press of a button, anywhere in the western world. He wanted to put all this at the disposal of the injured Chernobyl firemen and plant workers.

Gale contacted Arnold Hammer, the multi-millionaire son of Russian immigrant parents, who had had been on friendly terms with every Soviet leader since the revolution, and did a vast a amount of business with the Eastern Bloc. On Hammer’s recommendation, he got his invitation to fly to Moscow and help treat the victims of Chernobyl.

Gale concedes that a natural scientific curiosity as to the state of medicine in the Soviet Union in his chosen field accompanied his altruism. His description of what he found at Hospital Number 6 in Moscow, where the worst victims of the disaster were being treated, conjures up the graphic scenes depicted in Sarcophagus, the play written by Vladimir Gubaryev, science correspondent of Pravda.

The American was somewhat puzzled, in the event, at the readiness with which the Russian authorities agreed to accept his services. It was clear that they were capable of dealing with the situation medically. His contribution and that of his colleagues played a significant part in the treatment of the patients, but was far from being the paramount factor – despite the tendency, not just in US news media, to represent him as an intervening ‘Superman’. His Russian colleagues, for their part, welcomed the help he brought and even marvelled at the way that he was able to cut through red tape and get what was needed.

He wryly admits that his role might have been double-edged – from the Russian’s viewpoint. In view of the delays by the authorities in announcing the disaster coupled with a propensity to keep it off the front pages, it was clear that independent evidence would be extremely useful, to placate international opinion. In this respect, Gale’s arrival was a godsend. Hence the press conference in Moscow, when his work was finished, prior to his return to the USA.

Using the Croghan model, it is evident that a great deal of comment/analysis has been carried out to date on the Ukrainian nuclear disaster (Level 3). It is within the context of the other two levels that the model will be particlarly useful – based on how ‘conflict’, in relation to how meaning is assigned, is unravelled. The text (Level 2) would include all verbal comment and non-verbal human action bearing on the disaster. Each of the six actants might be considered individually – or holistically – as either text or intention. Significantly, there is a great deal of flexibility implicit in the model, which in summary, is concerned with how people apply meaning, a posteriori.

Using the Croghan model, it is evident that a great deal of comment/analysis has been carried out to date on the Ukrainian nuclear disaster (Level 3). It is within the context of the other two levels that the model will be particlarly useful – based on how ‘conflict’, in relation to how meaning is assigned, is unravelled. The text (Level 2) would include all verbal comment and non-verbal human action bearing on the disaster. Each of the six actants might be considered individually – or holistically – as either text or intention. Significantly, there is a great deal of flexibility implicit in the model, which in summary, is concerned with how people apply meaning, a posteriori.

Conclusion

The constraint that print media (newspapers, magazines etc.) in Ireland work under as regards coverage of events in Northern Ireland, is rarely emphasised. So fraught with controversy, indeed, was the prevailing topic, Section 31 of the Irish Broadcasting Authority Act 1960 and its alleged “draconian” implications for RTE (especially from its amendment by statutory instrument in 1977, until it was repealed by the then Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht, now President, Michael D. Higgins, in 1994), that it is assumed the newspapers, which were not governed by this legislation, were not affected.

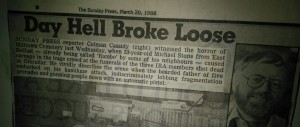

Assigned by his paper, the Sunday Press, to cover the funerals of the three IRA activists killed in Gibraltar by the British SAS in March 1988, the writer saw a unique opportunity to examine close-up the sub-culture surrounding the IRA in a way that was different. The paper’s deputy editor, Andy Bushe, was elated at the prospect of publishing the article that resulted. With less than one hour to go to deadline, however, the editor countermanded the order to run it. He asserted, in effect, wrongly, that it was “pro-IRA”. A new article was cobbled together by the deadline to save the day.14)cf. http://colmancassidy.com/death-in-the-rain/ The “Theory of Meaning” model could usefully examine many facets of this particular example, one might suggest.

Assigned by his paper, the Sunday Press, to cover the funerals of the three IRA activists killed in Gibraltar by the British SAS in March 1988, the writer saw a unique opportunity to examine close-up the sub-culture surrounding the IRA in a way that was different. The paper’s deputy editor, Andy Bushe, was elated at the prospect of publishing the article that resulted. With less than one hour to go to deadline, however, the editor countermanded the order to run it. He asserted, in effect, wrongly, that it was “pro-IRA”. A new article was cobbled together by the deadline to save the day.14)cf. http://colmancassidy.com/death-in-the-rain/ The “Theory of Meaning” model could usefully examine many facets of this particular example, one might suggest.

The model’s employment by Cullen for her thesis (Rape and Violence), was particularly useful in considering how meaning is assigned to violence in society. Just as it could with Northern Ireland, the model probed, inter alia, how the target of violence may be dehumanised by ideology or racial attitude.

Cullen notes (p.10) that the ability to legitimate violence in the name of patriotism is closely linked with holding power in society. Violence, in whatever form, can be used to exercise control and many unequal power relationships are ultimately maintained by the threat of violence (p.11).

Symbolic violence has been defined (Cullen 1990:1) as the negative portrayal of another subgroup or group for the purposes of defining the self group in a positive way.15)Cullen, Michelle, Rape & Violence, DCU, 1990, p.12.

That definition, one might suggest, is, by extension, tailor-made to fit the self-portrayal of Irish society by Dublin-based newspapers: in effect, the IRA, the North and Irish illegal emigrants in the USA are all mental aberrations, perhaps, that we should do well not to think about.

©

References

| 1. | ↑ | Fiske, John, Introduction to Communication Studies. London: Routledge, 1990, pp.2-5. |

| 2. | ↑ | Zeman, J., “Peirce’s theory of signs”, in T. Sebeok, (ed.), A perfusion of sign. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977, pp.22-39. |

| 3. | ↑ | Fiske, pp.43-44 |

| 4. | ↑ | Quoted by Liam Kelly, president of the Association International des Critiques d’Art (Irish Section) from his review of art in Northern Ireland, 1992 – delivered to The City as Art symposium in the National Gallery of Ireland on 6 December 1991. The symposium was sponsored by the Association as a contribution towards Dublin’s year as European City of Culture. |

| 5. | ↑ | cf. footnote (1); quote from Willat’s paper, Secret Language, read to the symposium. |

| 6, 7. | ↑ | Ibid. |

| 8. | ↑ | Kelly, op. cit. |

| 9. | ↑ | Kelly, op.cit. |

| 10. | ↑ | Kaufmann, R., and Broms, H., “A semiotic analysis of the newspaper coverage of Chernobyl in the United States, the Soviet Union and Finland.’ Semiotica, 1988, 70, 1/2, pp.27-48. |

| 11. | ↑ | Smith, Anthony, The Geopolitics of Information: How Western Culture Dominates the World. London: Faber and Faber, 1980, p.151. |

| 12. | ↑ | Croghan, M.J., Where did Limbo go? The analysis of a Real Theory of Meaning. NIHE Dublin, 1986. |

| 13. | ↑ | Cassidy, Colman Sunday Press, Dublin, 3 August 1986. |

| 14. | ↑ | cf. http://colmancassidy.com/death-in-the-rain/ |

| 15. | ↑ | Cullen, Michelle, Rape & Violence, DCU, 1990, p.12. |