Expressionism and the transformation of society

The Expressionist Artist, according to a contemporary critic, does not portray, but experience, does not reproduce but shape, does not offer facts but visions.

COLMAN CASSIDY explores what, if anything, this stress on the subjectivity of the artist has to do with the expressionists’ stated goal: the transformation of society.

INTRODUCTION

Expressionist painting in Germany as the pinnacle of high modernism came dangerously close to being adopted by the Nazis after Hitler came to power in 1933. The Nazis, in their early years had attacked the whole modern movement in art as degenerate – “a plot by Jews and Bolshevists to undermine German self-confidence”. That was the line taken by Alfred Rosenberg’s Kampfbund in 1927.1)Ascherson, Neal, “The Fuhrer’s Freak show”, in The Independent on Sunday (Review section) 1st March, 1992 But in 1933, a powerful group of pro-Nazi critics recognised that expressionist art could be used to bring about the “transformation of society” the party required – and argued that the propagandist art they needed was already there. “It cannot be denied that it was the New Art itself which prepared the way for the national revolution,” one of these critics asserted.

By ‘New Art’, he meant the work of expressionist painters such as Erich Heckel, Otto Mueller, Franz Marc, Emile Nolde, Paul Klee and Lyonel Feninger, Ascherson contends. The “transformation of society” which the Nazis sought to accomplish through the vilification of abstract art was a far cry from the expressionists’ stated goal, namely, the transformation of society.

It appears that the argument that raged within Nazism over the New Art was part of a power struggle between Goebbels as propaganda minister and Rosenberg – that is, between the populist and authoritarian wings, the latter dominated by the SS.

In July 1937, the first “Exhibition of Degenerate Art”opened its doors, in Munich. It featured a total of 650 workers from early expressionism to contemporary work by Beckmann, Dix, Grosz, Klee and the Russian-born Kandinsky. These works of art were not aimed at party ideologues: they were viewed by the German masses who were encouraged to believe that all the problems in their lives could be laid at the door of “Jewish business, negro jazz, Russian atheists and mincing perverts”.2) Ibid.

This perversion of the expressionists’ stated goal of transforming society, ironically, was to have fundamental implications for the international modern art movement – after the war. Dix, Nolde and other artists went to ground in Germany and survived. But notable artists such as Beckmann and others made their way to the USA where as painter-teachers they fomented the eruption of abstract expressionism in the west that was to come about over the next few decades.

After 1945, abstraction became identified as the visual language of “liberty and democracy” while figurative art became more closely associated with totalitarianism.3)Ibid. What is especially remarkable is the seminal contribution made by expressionism to that eruption in modern art, given that the movement’s raison d’être was an intense subjectivism that lacked a vocal centre. 4)Cardinal, Roger, Expressionism. London: Paladin, 1984, p.129

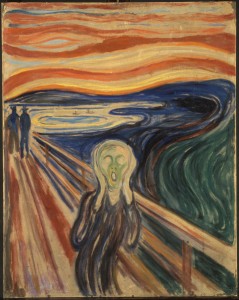

The concept of man as an alienated being trapped in an intolerably uncertain universe, is the theme of The Scream, Edvard Munch’s powerful expressionist monologue in paint. Painted in 1893, at a time when Nietzsche’s philosophy was becoming extremely influential, The Scream may be seen as a powerful subjective metaphor for the condition of modern man. In that sense, at least, it seems particularly relevant today, given the changes that have overtaken Germany and Central Europe and the Soviet Union within a very short timescale. Today’s political/cultural “map” of Europe bears an uncanny resemblance to the way things were in the Wilhelminian era. Munch’s painting (transposed into poetry, as Scream, by August Stramm) is one of the key images of expressionist art – depicting a skeletal lonely figure standing on a jetty in awesome swirling surroundings, the gaping mouth held wide in a shriek that seems to resound across the surrounding emptiness. What does it mean? Cardinal suggests it could be an expression of “metaphysical anguish” at being severed from the natural world; social torture at being separated from other people – or even psychotic frenzy: “Whatever statement we apply as a caption to this image, its power as a non-verbal expression of real feeling is incontrovertible.”5)Cardinal, pp.36-38

This essay treats, in the main, with German expressionism in its varying forms as the zeitgeist of the first two and a half decades of the 20th century, its politics and later decline. The essay’s nuances are developed by reference to the political and cultural exigencies dating from the 1890s (notably, though not exclusively, Nietzschean/left-wing), and progressing in various forms throughout the period under review.

Notable artists’ groups founded in Germany during the first decade of the century and which acquired, a posteriori, the label Expressionismus, included Die Brucke (Dresden 1905), Neue Sezession (Berlin 1910) and Blaue Reiter (Munich 1911). On the literary front, the movement embraced a number of distinguished poets, notably the circle involved in Kurt Hiller’s Neuer Club (1909), such as Georg Heym and Jakob van Hoddis, as well as a number of first-rate dramatists – including for a time, Bertolt Brecht. Indeed, expressionism may be said to have “cross-fertilised” music to architecture, even to cinema. Such a process was starkly evident in the collaborations of various activists with Der Sturm and Die Aktion, the two periodicals that gave direction to the movement.

Der Sturm was the journal launched in 1910 by Herwarth Walden, through which the emerging opposition to Wilhelminian culture finally found a concerted voice that ultimately came to be known as Expressionism.6) Taylor, Seth, Left-Wing Nietzscheans: The Politics of German Expressionism, 1910-1920, Berlin/NY: 1990, p.44 It strongly championed individual artists. The first artist it promoted was Oscar Kokoschka, the Viennese painter-draughtsman and Walden’s friend and collaborator. Then came the Brucke group, but it was not until 1912 that Walden was able to stage the first of his renowned Sturm Gallery exhibitions – featuring Kokoschka and Blauer Reiter.7)Dube, Wolf-Dieter, The Expressionists. London: Thames & Hudson, 1972, pp.159-160

Franz Pfembert’s magazine, Die Aktion (and the publishing house of that name),founded 1911, was the more politically focused of the two – criticising as it did the drift towards war in the period 1911-14.8)Timms, Edward (ed.), Unreal City. NY: St. Martin’s Press, 198, p.111 Pfembert, who had a long history of political involvement going back to Georg Landauer’s anarchist group at the turn of the century, continuously castigated the Wilhelminian bourgeoisie for sacrificing liberal ideals in deference to a declining Jünger caste. It is significant that Die Aktion accurately predicted – well in advance – that the Social Democratic Party, SPD, would abandon its revolutionary principles for the national interest. Pfembert was all too aware that despite the attraction of a socialist alternative held out for a disillusioned young intelligentsia, the SPD’s unrelieved materialist doctrine was not the answer to the positivism which in the main they eschewed.9)Taylor, pp.22-23

Cardinal’s otherwise excellent critique fails to pay much attention to the role of politics in the development and later evolution of expressionism. Within his comprehensive analysis, there is but scant reference of the holistic role played by Nietzschean antipolitics in the movement’s early gestation. The relative absence of Nietzsche in studies of expressionist politics is accounted for by the fact that real political engagement came about only in the movement’s late period – when Nietzsche’s influence was already on the wane.10)Taylor, p.14

There were, nonetheless, undeniable echoes of Nietzsche in Cardinal’s recognition of expressionism’s “…impulsive stand against the mechanical, positivist arguments of bourgeois civilisation. Expressionism hated the ideology of money, calculation, mechanisation. It hated imperialism and capitalism, it hated patriotism and the class system, it hated generals as it hated fathers. And so, when Hitler became dictator, expressionism at once recognised the ultimate antithesis to itself and saw no possibility of compromise.”11)Cardinal, p.127

POLITICS

The decline of naturalism in the 1890s had induced the young intellectuals of that time to embrace the aesthetic philosophy of Nietzsche, which Taylor identifies as the “bridge to Expressionism”. Nietzsche articulated a cultural decadence that had a strong attraction for them. 12)Taylor, p.28

Peter Bergmann, in his book, Nietzsche: the Last Antipolitcal German, (Indiana University Press, 1987), seeks to reconcile – hitherto irreconcilable – views on Nietzsche and politics. Nietzsche’s antipolitics, far from being an indifference to politics, Bergmann argues – in refutation of Walter Kaufmann’s assertion in Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist (4th ed., Princeton University Press, 1974) – actually meant that he was politically involved in the affairs of his day: Nietzsche’s politics took the form, however, of resistance to encroachment by the state on the cultural life of the nation.

Nietzschean hostility to liberalism per se arose from the fact that “German liberalism had betrayed its cosmopolitan origins and embraced nationalism and imperialism”. Thus Nietzsche’s antipolitics, far from denoting indifference, was targeted against those developments in German history that eventually were to culminate in fascism. In Georg Landauer’s opinion (according to his biographer, Eugene Lunn), it was Nietzsche’s lack of understanding of the social world that stopped him from seeing that socialism was in fact the logical realisation of his teachings.

Landauer’s contribution was significant because of the leading part he was to play in establishing the “ethical socialism” of the Independent Socialist movement as an antidote to the “vulgar materialism” espoused by the SPD leadership.13)Taylor, pp.28-29 Landauer was among the first to adopt Nietzschean vitalism as the way to overcome his own passive aestheticism. (Vitalism is the generic name for a variety of irrational trends that emerged in Europe in the early 20th century). Another propounder of vitalism was Georg Simmel, professor of sociology and philosophy at the University of Berlin before the First World War who had “mediated Nietzsche’s philosophy to both the young Lukacs and the Expressionists”. 14)Taylor, pp.8-9, 28-29

For the Marxist philosopher Georg Lukacs, Nietzschean vitalism was to become just another form of decadent irrationalism, buttressing the decline of capitalism. Expressionist opposition to capitalism was much too idealistic and subjective for Lukacs. In 1934, Lukacs, in a seminal essay, “Expressionism: Its significance and decline” (Essays on Realism, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1980), precipitated an exchange of views within Marxism – most relevantly for the purpose of this essay, between Lukacs and his former friend, Ernst Bloch. (Lukacs’s views were to subsequently bring him into conflict with Bertolt Brecht and Theodor Adorno).15)Taylor, Ronald (trans. ed.), Aesthetics & Politics. London: NLB, 1977, pp.60-85; pp. 151-176

German expressionism provided a more propitious framework than French surrealism for such a debate, Jameson notes. Lukacs, one of the major figures in 20th century Marxism, effectively turned the debate into a discussion on realism.16)Jameson, Frederic, “Reflections in Conclusion”, Aesthetics & Politics. NLB, 1977, pp. 196-213 Bloch defended expressionism against Lukacs’s attempts to portray it as a forerunner of fascism – citing the fact that the Nazis had dubbed expressionist art degenerate. Neither was expressionist pacifism prior to the revolution of 1919 mere pseudo-opposition, since German politicians were on record as identifying it as a significant threat. For that reason alone the subjectivist nature of expressionism could not be equated with the worldview of the imperialist bourgeoisie. For Lukacs, only the classical was healthy, the romantic tradition that evolved after Marx being “decadent”. It followed from this that all modern art must be rejected as simply a reflection of bourgeois decline. His arguments against irrationalism and (post-Marx) romanticism were, essentially, to the effect that they were not Marxist. Lukacs was able to discover in Marxism the idealistic foundations of that philosophy which had been forgotten – or at least overlooked – by the turn of the century.

For the expressionists, vitalism achieved the same objective. Taylor points to a crucial point that Bloch seems to have overlooked in the debate, namely, that it would have been impossible for the expressionists to embrace Marxism prior to the end of the war: “Until then, Marxism was far too (much) under the sway of positivism and the vulgar materialism which the majority of the intelligentsia rejected.” There was no Marxist revolutionary ideology at the time capable of supporting their goals.17)Taylor, pp.10-12

Nonetheless, the political denouement of German expressionism had undoubtedly revealed a failure to realise the glorious destiny predicted for the movement, emanating from the white heat of Nietzschean vitalism. This failure, indeed, was predicated from within Nietzsche’s antipolitical philosophy. In practice, the two themes – the elite individualist critic of culture versus the artist as social activist – were to prove irreconcilable, as Heinrich Mann had deduced, earlier: “Their own elite individualism undermined their chances of political influence while their notion of a vital culture precluded the political engagement necessary to bring that culture about.”18)Taylor, p.14

The explanation for the politics that developed in later expressionism was the failure of the cultural revolution on which so much had been staked. Ultimately, it was “to prove impotent in a world war in which the Expressionists themselves were dragged off to the trenches”. By 1916, pacifism had become the norm among the intelligentsia. Among the expressionists who had died at the front were Stadler, Lichenstein, Stramm, Trakl, Macke, Marc and Morgner. The timid policies of the SPD, meanwhile, were subsequently overtaken by the more direct methods espoused by revolutionaries such as Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg – inducing expressionists to follow the very path trodden by Georg Lukacs before them, from cultural revolt to Marxism.19)Taylor, pp.13-14; Cardinal, p.48

This was exemplified in the failure of Kurt Hiller’s Activist movement to turn Nietzsche’s philosophy into the cornerstone of political activism – through Hiller’s own inability to eschew elitism. Subsequently, the Berlin Dadaists were to reject expressionism and unambivalently embrace Marxist politics because of this very phenomenon. Ironically, this initiative was seen as being less supportive of Georg Lukacs’s later denouncement of Nietzschean irrationalism than a condemnation of what they saw as expressionism’s elitist links with the classical tradition (espoused by Lukacs) – identified by the Dadaists as the true source of German militarism.

Taylor notes that most of the expressionists continued to defend Nietsche against his right-wing interpreters, even as they abandoned his philosophy.20)Taylor, pp.14-15 Left-wing intellectuals such as Bertolt Brecht and Heinrich Mann were profoundly uncomfortable between 1919-30, Sontheimer suggests. They discovered that the new Weimar did not live up to their expectations, its realities far removed from the social and democratic republicanism that the left had dreamed of after the war.

Writers on the right such as Ernst Jünger and Oswald Spengler (Decline of the West) did everything possible to overthrow Weimar democracy and introduce a strong ‘unliberal’ brand of Prussian “socialism” – through a new type of Caesarian regime that would wipe out the weaknesses of liberal democracy. Somewhere in the middle were the Vernunftrepublikaner (rational republicans) such as Heinrich Mann’s younger brother, Thomas, who acknowledged that nostalgia for the empire was ridiculous, but could not see that the Republic might deserve wholehearted support.21)Sontheimer, Kurt, “Weimar Culture” in Laffan M.(ed.), The Burden of German History 1919-45, pp.2-9

Heinrich (born 1871), who abandoned aestheticism for politics, yet was also a seminal influence for the expressionists, was one of the writers on the left who was unable to reconcile Nietzsche and socialism. He had openly distrusted the strong Nietzschean vogue of the 1890s, referring dismissively to “the little poets who have made Nietzsche into a fashionable philosopher, making a just appraisal impossible”.22)Taylor, p.31

An important “footnote” – directly linked to expressionism because of Heinrich Mann’s influence on the movement – is the public disagreement that took place between the two brothers. In an essay on Zola (who had championed Dreyfus), Heinrich Mann trenchantly attacked his brother’s conservatism. Thomas Mann’s reply in his Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, is a good summary of the deeply held but largely unconsidered opinions espoused by intellectuals of the Second Reich, concerning their political and social functions.23)Ridley, Hugh, “The Culture of Weimar: Models of Decline”, in Laffan, M. (ed.), The Burden of German History 1919-45, pp.11-30

Ridley sees the Thomas Mann book as a crucial text for the transfer of pre-1914 attitudes into the Weimar Republic, whose establishment coincided with its appearance – and for demonstrating the continuity across the divide of the war.24)Ridley, p.16 The younger Mann publicly retracted his position in 1922, became reconciled with his brother and a champion of Weimar democracy. He was vilified as a ‘Judas’ for betraying the German spirit to political pragmatism, incurring the wrath of strong nationalist lobby then paving the way for the debut of Nazism.25)Ridley, p.19 Ironically, in view of this later retraction, (as with Nietzsche), Thomas Mann’s Reflections…contributed to the “intellectual armoury” of the reaction that was to engulf the Weimar Republic’s attempts to introduce a democratic literature.26)Ridley, p.17

LITERATURE & ART

For Sabarsky, Expressionism was the most influential of all movements in 20th century art: it was above all else, a protest against the bourgeoisie, against aestheticism, and in the visual arts, against late impressionism – as well as an expression of a new sense of life.27)Sabarsky, Serge (ed.), Graphics of the German Expressionists. London, 1986, p7

[The Sabarsky-edited Graphics of the German Expressionists is a useful introduction to the works of artists such as Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Lyonel Feninger, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erick Heckel, Otto Mueller, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and Karl Schmidt-Rotluff.]

The expressionists penetrated the world of outer reality in search of the nucleus of meaning. They saw themselves as “prophets of a new grand order”, which they proclaimed in their poetry, plays and paintings.28)Selz, Peter, “The Portrayal of Experience” in Graphics of the German Expressionists. London, 198 pp.16, 22

Cardinal uses the analogy of the mystical ecstasy experienced by Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin in The Idiot – just before an epileptic attack – to illustrate what he calls the expressionist paradox: that extremes combine in involuntary combinations which then take on meaning and necessity: “The loathsome sense of utter wretchedness which is the subjectivity’s response to undeserved pain or anxiety, is balanced by the premonition of access to sensations of transcendent bliss in which the subjectivity feels itself to be intense and distinct, while at the same time fused with the dynamic pulse of universal existence.”29)Cardinal, pp. 124-125

Apart from the long list of aesthetic influences that itsought to negate, expressionism had as its goal the overthrow of an equally long list of moral and social determinants. It was therefore less exclusively an artistic rebellion than a major movement on all fronts of the “existential struggle”.

It embraced movements as diverse as Arnold Schonberg’s music and the eurhythmic dance of Isadora Duncan, the architecture of Bruno Taut – founder of the Bauhaus guild of artists – as well as the plays of August Strindberg and Georg Kaiser and the versatile painter-sculptor-graphic artist-dramatist, Ernst Barlach. In cinema, the emphasis on violence, both sexual and homicidal, was striking – as in the filmed works of Frank Wedekind, Robert Wiene, Fritz Lang, Friedrich Murnau or Oskar Kokoschka (also a painter).

Soutine’s painting, Carcass of Beef, (1925) is a superb example of expressionist exoticism. The picture represents a rotting side of meat – that hung in the Russian-born Soutine’s studio for weeks, while he poured buckets of fresh blood over it to preserve its colour. 30)Ibid., pp.26, 28-30, 31, 33, 44; Robertson, J. G. A History of German Literature. London: Blackwood, 1968,. pp.541-561

[Soutine’s Man Walking the Stairs in the National Gallery of Ireland, confronts the viewer with a compelling sense of isolation and alienation. The overall effect is one of tension, foreboding and menace. Involvement in the picture is accomplished by the elimination of space, the use of strident (predominantly green) colours and the extreme plasticity of the image – painted in a spontaneous impasto technique.]

It is against this background that Kasimir Edschmid’s assertion that expressionist artists “do not work as photographers but are overcome by visions”, is relevant: “We do not try to catch the momentary effect of a situation but its eternal significance; are concerned not with descriptions but lived experience. We do not reproduce, but create…in an atmosphere of continual excitement.”31)Edschmid, Uber den Expressionismus in der Literatur. Berlin, 1919, p.52

Edschmid (born 1890), is historically important as a pioneer of the movement, not least because of his literary manifestos and the early narratives collected in his volumes, Die sechs Mundungen (1915) and Das rasende Leben(1916).32)Hatfield, Henry, Modern German Literature: The Major Figures in Context. London: Edward Arnold, 1966, p.80

Kurt Pinthus took the Edschmid critique a stage further, in his introduction to Menschheitsdammerung, the major anthology of expressionist verse: “Never was …the principle of l’art pour l’art so flouted as in this poetry, which we call…expressionism because it is all eruption, explosion, intensity – must be, to break through every hostile crust.33)Pinthus, K., Menschheitsdammerung. Berlin, 1919, pp.xivf

Poems such as Jakob van Hoddis’s End of the World (1911) were to set the tone for Menschheitsdammerung (Twilight of Humanity). Poets such as Trakl and Heym, meanwhile, evoked moonscapes of the psychic state, such as in the former’s Psalm:

“There is a light, blown out by the wind. There is a moorland tavern from which a drunkard departs in the afternoon. There is a vineyard, burnt and black with holes full of spiders. There is a room, whitewashed with milk. The madman has died.”34)Trakl, G., Das dichterische Werk. Munich, 1972, p.32 Trakl, who was to kill himself in 1914 – after an horrific night tending badly wounded soldiers, without medical supplies – evinces an extremely negative view of reality that reveals a crisis of self identified by Cardinal as a common starting-point in the expressionist problematic of sensibility.35)Cardinal, pp.33, 44-45

ART GENESIS

As early as 1889, Edvard Munch, the Norwegian painter who was later to have such a dynamic impact on the German Expressionists, had asserted during his first visit to Paris that henceforth humans should be painted as living beings who breathed, loved and suffered – no longer as figures in a room’s interior, reading and knitting.36)Selz, p.15

For the Germans, Munch had a seminal role along with Van Gogh – from both of whom expressionist painting in Germany evolved its raison d’être. The term, in the French sense, originally was meant to denote a differentiation between Matisse – who ironically, was enormously important, too, for the development of “German” expressionism – and other painters from impressionism.37)Taylor, p.37

The seminal usage in Germany of the term, expressionism – as a distinctive art movement – is generally traced to the opening of the 22nd exhibition of the Berliner Secession in April 1911. In the preface to the exhibition’s catalogue, no reason was given for appending the term, Expressionisten, to the young artists from Paris – a group which included Braque, Derain, Picasso, Marquet, Vlaminick and Dufy, who would normally be described as Fauves or Cubists.38)Dube, p.18

Extensive media coverage of the event showed that the press critics assumed that the term was already in use outside Germany: “…that it was an established French designation of a new group or an allusion to a new trend in art.” The term quickly became popular with the German public – though not as an expressly German phenomenon. It was used again in Cologne, in 1912 – at the international “Sonderbund” exhibition – to designate an exciting new trend in European painting.39)Werenskiold, Marit, The Concept of Expressionism. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget, 1984, pp.5-6

In March of that year, when Herwarth Walden put on the first exhibition at his Sturm-Galerie in Berlin, he showed “Der Blaue Reiter, Franz Flaum, Oskar Kokoschka, Expressionisten”. On that occasion, too, ironically, Expressionisten referred only to the French artists.40)Dube, p.18

The Blue Rider movement contained both an aesthetic and an ethical programme aimed at the overthrow of materialism in favour of spiritual harmony.41)Cardinal, p.141n

Franz Marc, who co-founded the Blue Rider with Kandinsky, summarised this programme thus in the same edition of the Almanac: “In this age of the great struggle for the new art, we are fighting as ‘wild beasts’ unorganised levies against an old organised power. The battle seems unequal, but in matters of the spirit, it is never the number but the strength of the ideas that conquer. The dreaded weapons of the ‘wild beasts’ are their new ideas; these kill more effectively than steel and break what was thought to be unbreakable.”42)Dube, p,20 The ‘wild beasts’ he identified as the Brucke in Dresden, the Neue Sezession in Berlin and the Neue Vereinigung in Munich.

In the period 1910-14, German art was marked by the same Paris-orientated internationalism that was evident in the rest of contemporary Europe – and which gave rise to deep resentment in nationalist circles, with the approach of the Great War. After the outbreak of war in August 1914, German artists and intellectuals severed their contacts with France and in the main espoused a form of nationalism glorifying Germany.

As a Russian, Kandinsky had to leave Germany while his young artist colleagues were mobilised for war service against their former friends in France and Russia.43)Werenskiold, pp.49, 50

Paul Fechter’s Der Expressionismus, published in Munich, 1914, is particularly relevant as the first monograph on the subject. This book had a major impact on the development of a new German national concept of Expressionism – as a specifically German movement, “with deep roots in the soul of the German people and in German medieval culture”.

Fechter (1880-1958) was in the same age group as the Brucke artists – Nolde excepted – and as a Dresden-based art critic (1905-10) and later in Berlin had followed closely the group’s development.44)Ibid., pp.50, 51, 177n, 178n

It is significant that the only artists that Fechter names in his “Expressionismus” chapter in the book apart from Kandinsky, Marc and Kokoschka and Pechstein are the Brucke members, Heckel, Kirchner and Schmidt-Rotluff. Edvard Munch earns a brief mention as the inspirer of German Impressionism of the 1890s, whereas Matisse is completely ignored – although several reproductions of his work are included as illustrations.45)Ibid., p.51

Werenskiold argues that Fechter’s work – whether consciously or not – provided the “best imaginable defence” for the new art in the Germany of his day and was instrumental in leading Expressionism to “a rapid victory”.

By presenting it as primarily a Germanic movement, a manifestation of the primordial ‘Gothic Soul’ of the German people, Fechter provided a formidable apologia for the new art.

“It was in the war years 1914-1918 that ‘Expressionismus’ became the great, all-embracing slogan of German cultural life, a banner to which a new generation of artists, writers and musicians rallied in desperation or exalted enthusiasm.”46)Ibid., p.51

Taylor notes that the relative absence of Nietsche in studies of expressionist politics is accounted for by the fact that real political engagement came about only in the movement’s later period, after the war – when Nietzsche’s influence was already on the wane. The explanation for the politics that developed in later expressionism was the failure of the cultural revolution on which so much had been staked. Ultimately, it was “to prove impotent in a world war in which the Expressionists themselves were dragged off to the trenches”. The timid policies of the SPD were subsequently overtaken by the direct method espoused by revolutionaries such as Karl Liebknecht and Rosa

Luxemburg – inducing expressionists to follow the very path trodden by Georg Lukacs before them, from cultural revolt to Marxism.47)Taylor, pp.13-14 It is, perhaps, remarkable that only a mere handful out of the dozens of expressionist artists and writers welcomed the onset of national socialism. So naturally repellant, indeed, was the Nazi ideology for the vast majority that it is, as Cardinal says, “almost possible to define the former purely as the inverted version of the former”.48)Cardinal, pp..127, 142n Among the few exceptions were the acerbic nihilist, Gottfried Benn, who was among the first generation of writers for Der Sturm.49)Taylor, p.9 The artist, Emil Nolde, also welcomed the Nazis’ special brand of nationalism and even joined the party in 1933, but came to realise the error of his ways before long. Ironically, Nolde’s works, along with those of many other leading expressionists, were removed from museums by the Nazis, confiscated or sold abroad. He was forbidden to paint and turned his hand to watercolours, which he termed “unpainted pictures”. Ironically, some regard these waercolours as the pinnacle of his oeuvre.50)Sabarsky, p.164

CONCLUSION

Cardinal sees the movement’s failings as: loss of momentum through the lack of a vocal centre; also, its immoderate limits through “inflating gesture into unbecoming exaggeration, traducing primal sincerity and offering super-charged sham”. Expressionist poems, he contends, often seem no more than noisy and provocative; its films departed from psychological suspense and drifted into the genre of surface thrills. Its plays were often too jerky, its paintings too frantic.

Such failings, however, could be excused in a movement that was not only so widespread and ambitious, but was also so marvellously enthusiastic: “What matters is that a central corpus of major works was produced which is still capable…of imparting values to us.”51)Cardinal, p.129

For many people today, The Scream is the apotheosis of German expressionist art painted by German expressionism’s (estranged) Norwegian-born “father”. The American critic, Frederic Jameson, refers to the painting as “the canonical expression of the great modernist thematics of alienation, anomic, solitude and social fragmentation and isolation, a virtually programmatic emblem of what used to be called the age of anxiety”.52)Jameson, Frederic, Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. 1986 – mimeograph: UCD Library

The notion that the alienated subject depicted in The Scream is trapped in an intolerably uncertain universe represents one extreme of the expressionist conception of man. It is one of the key signifiers (in a semiotic sense) of expressionist art – as depicted in the silent scream of the cadaverous earless monad standing starkly alone in the world, despite the two neutral figures in the background.53)Cardinal, 36-38Is it inconceivable that Jameson (1986) could be premature in his contention that The Scream is a virtual deconstruction of the very aesthetic of expression which seems to have dominated much of the “high modernism” that has vanished – for practical and theoretical reasons – in the world of the post-modern?54)Jameson, op. cit. A profound sense of déjà vu is induced by Munch’s seminal painting, which probably relates to the series of “coincidences” that appeared to turn the last decade of the 20th century – in a newly reunited Germany – into a virtual series of mirror-imagesof the last decade of the 19th.

In that sense, at least, The Scream somehow seems to present as a terrifyingly appropriate exclamation mark for our own time. The question remains: does The Scream (expressionism)reveal a profound view of the human condition and question our place in the cosmos? If it does, is it not fair to assume that the expressionist task of transforming society, continues?

Colman Cassidy ©

References

| 1. | ↑ | Ascherson, Neal, “The Fuhrer’s Freak show”, in The Independent on Sunday (Review section) 1st March, 1992 |

| 2. | ↑ | Ibid. |

| 3. | ↑ | Ibid. |

| 4. | ↑ | Cardinal, Roger, Expressionism. London: Paladin, 1984, p.129 |

| 5. | ↑ | Cardinal, pp.36-38 |

| 6. | ↑ | Taylor, Seth, Left-Wing Nietzscheans: The Politics of German Expressionism, 1910-1920, Berlin/NY: 1990, p.44 |

| 7. | ↑ | Dube, Wolf-Dieter, The Expressionists. London: Thames & Hudson, 1972, pp.159-160 |

| 8. | ↑ | Timms, Edward (ed.), Unreal City. NY: St. Martin’s Press, 198, p.111 |

| 9. | ↑ | Taylor, pp.22-23 |

| 10, 18. | ↑ | Taylor, p.14 |

| 11. | ↑ | Cardinal, p.127 |

| 12. | ↑ | Taylor, p.28 |

| 13. | ↑ | Taylor, pp.28-29 |

| 14. | ↑ | Taylor, pp.8-9, 28-29 |

| 15. | ↑ | Taylor, Ronald (trans. ed.), Aesthetics & Politics. London: NLB, 1977, pp.60-85; pp. 151-176 |

| 16. | ↑ | Jameson, Frederic, “Reflections in Conclusion”, Aesthetics & Politics. NLB, 1977, pp. 196-213 |

| 17. | ↑ | Taylor, pp.10-12 |

| 19. | ↑ | Taylor, pp.13-14; Cardinal, p.48 |

| 20. | ↑ | Taylor, pp.14-15 |

| 21. | ↑ | Sontheimer, Kurt, “Weimar Culture” in Laffan M.(ed.), The Burden of German History 1919-45, pp.2-9 |

| 22. | ↑ | Taylor, p.31 |

| 23. | ↑ | Ridley, Hugh, “The Culture of Weimar: Models of Decline”, in Laffan, M. (ed.), The Burden of German History 1919-45, pp.11-30 |

| 24. | ↑ | Ridley, p.16 |

| 25. | ↑ | Ridley, p.19 |

| 26. | ↑ | Ridley, p.17 |

| 27. | ↑ | Sabarsky, Serge (ed.), Graphics of the German Expressionists. London, 1986, p7 |

| 28. | ↑ | Selz, Peter, “The Portrayal of Experience” in Graphics of the German Expressionists. London, 198 pp.16, 22 |

| 29. | ↑ | Cardinal, pp. 124-125 |

| 30. | ↑ | Ibid., pp.26, 28-30, 31, 33, 44; Robertson, J. G. A History of German Literature. London: Blackwood, 1968,. pp.541-561 |

| 31. | ↑ | Edschmid, Uber den Expressionismus in der Literatur. Berlin, 1919, p.52 |

| 32. | ↑ | Hatfield, Henry, Modern German Literature: The Major Figures in Context. London: Edward Arnold, 1966, p.80 |

| 33. | ↑ | Pinthus, K., Menschheitsdammerung. Berlin, 1919, pp.xivf |

| 34. | ↑ | Trakl, G., Das dichterische Werk. Munich, 1972, p.32 |

| 35. | ↑ | Cardinal, pp.33, 44-45 |

| 36. | ↑ | Selz, p.15 |

| 37. | ↑ | Taylor, p.37 |

| 38, 40. | ↑ | Dube, p.18 |

| 39. | ↑ | Werenskiold, Marit, The Concept of Expressionism. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget, 1984, pp.5-6 |

| 41. | ↑ | Cardinal, p.141n |

| 42. | ↑ | Dube, p,20 |

| 43. | ↑ | Werenskiold, pp.49, 50 |

| 44. | ↑ | Ibid., pp.50, 51, 177n, 178n |

| 45, 46. | ↑ | Ibid., p.51 |

| 47. | ↑ | Taylor, pp.13-14 |

| 48. | ↑ | Cardinal, pp..127, 142n |

| 49. | ↑ | Taylor, p.9 |

| 50. | ↑ | Sabarsky, p.164 |

| 51. | ↑ | Cardinal, p.129 |

| 52. | ↑ | Jameson, Frederic, Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. 1986 – mimeograph: UCD Library |

| 53. | ↑ | Cardinal, 36-38 |

| 54. | ↑ | Jameson, op. cit. |