Lebanon: Irish courage under fire is praised

Sunday Press 24 March 1985, page 1

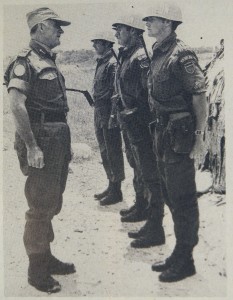

The Cork-born commander of the United Nations Force in the Lebanon, UNIFIL, General William Callaghan, yesterday paid tribute to the work of the Irish troops in this volatile region and said people at home should realise that this was not a civilian’s but a soldier’s mission.

The Cork-born commander of the United Nations Force in the Lebanon, UNIFIL, General William Callaghan, yesterday paid tribute to the work of the Irish troops in this volatile region and said people at home should realise that this was not a civilian’s but a soldier’s mission.

General Callaghan, who has the difficult task of directing the operations of the UNIFIL force in the face of extreme provocation, told me: “I have great respect for the maturity and common sense of the private at his observation post who must assess risks every day and make the right decision.”

“It’s important that people at home should understand this,” he went on. “The achievements and performance of Irish soldiers in the Lebanon have been truly phenomenal and it is internationally recognised, after two decades of peacekeeping around the globe, that they are among the most experienced in the world. The Lebanon is a great training ground for our men.”

Gen. Callaghan pointed to the fact that when the Irish troops arrived with the first UNIFIL force in 1978, there were 16,000 people living in their part of south Lebanon. Four years later there were 250,000 living there and after the 1982 Israeli invasion a further 150,000 moved in because of the UNIFIL presence. “Schools are opening and, believe it or not, house-building and construction are going on at an unprecedented rate,” he told me. “The local people want us to stay.”

The general’s remarks came in the wake of a most difficult week for the Irish troops. They were involved in a four-hour gun battle with Israeli-backed militia and on Friday they were engaged in an angry confrontation with Israeli soldiers who fired very close to Irish troops outside the village of Haris.

It appears that the Israeli strategy is to force the UNIFIL force, especially the Irish, out of the area they now occupy, to move them forward towards Beirut, so that their own Lebanese puppet army can control the region and provide a buffer zone with northern Israel.

Lebanon exclusive: BETWEEN THE BULLETS IT’S TALK, TALK…

From Colman Cassidy in ROSH NA NIKRA

At exactly 0800 hours ‘UNIFIL 1’, the big white Chevvy with a blind on the back window, rolls up to the heavily-guarded Israeli border at Rosh na Nikra. Inside is General William Callaghan, known to everyone out here who is not an Israeli as the Force Commander.

One of the two women soldiers on duty at the barrier smiles fleetingly in response to his modulated “Shalom”. She wears a machinegun on her back as dispassionately as any waitress in the Bronx might carry an order book.

I observe all this as I approach the checkpoint on foot to cross the border into Lebanon. My reception is less cheery and more prolonged, but that’s another story.

Last night, in Nahariyya, a seaside town built by German Jews half a century ago, I’d met some senior Irish officers attached to UNIFIL headquarters at Nacquora.

They were genuinely fond of General Callaghan and spoke of him as someone at the pinnacle of his career, whose extraordinary qualities as military leader, diplomat, intellectual, even politician, were formally recognised by the UN – and in particular by the ten nations whose forces on the ground in Lebanon he controls.

Personalised

General Callaghan has delayed his helicopter flight to Beirut, where he was meeting General Aoun, commander-in-chief of the Lebanon army, to meet me, at very short notice

His is quite a personalised job, he says: “You cannot delegate your own interpretation of nuances,” in a part of the world where talking, even for its own sake, can often mean the difference between life and death.

His is quite a personalised job, he says: “You cannot delegate your own interpretation of nuances,” in a part of the world where talking, even for its own sake, can often mean the difference between life and death.

This is no throwaway line. While a young soldier from Ballyfermot or Crossmolina will employ psychology, tact and a maturity well beyond his years to defuse a potentially lethal situation at his checkpoint, often several times a day, the Force Commander, too, is talking.

He talks to General Aoun, to the Irish-born Israeli President Chiam Herzog and Prime Minister Peres, and in particular to the Israeli defence minister, Yitzhak Rabin. He talks to President Amin Gemayel, the Christian head of state in Lebanon, whose father founded the Phelangist Party in the 1930s, and to the Lebanese Prime Minister Rashid Karami, a Moslem.

He is on first-name terms with a good many muktahs around the country, who are the local representatives of all shades of Islamic opinion in Lebanon. And he talks to the United Nations Secretary General, and especially to Brian Urquhart, the Under-Secretary General. All of this I’d gleaned from his fan club the night before in Nahiriyya, among whom he is known as “Bull” Callaghan.

Invasion

General Callaghan dodges my question about Conor Cruise-O’Brien’s recent assertions over the diminishing marginal futility of the UNIFIL role, and more particularly Ireland’s, in the Lebanon. He cannot comment on political matters, he says. He recalls, however, that O’Brien had written an interesting piece in the Jerusalem Post, just after the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon.

On the invasion itself, he is unequivocal: it was the wrong move – a reaction to the attack in London on the Israeli ambassador: “Between July 1981 and June 1982 there was a cessation of the fire between Israel and the PLO. Since UNIFIL went in, in 1978, there were in fact only two recorded incidents of a physical violation of the border. The first was when a small party of Palestinians attacked a kibbutz in northern Israel (Galilee) in 1980 and killed somebody. There was no indication that they came through UNIFIL lines. But even if they did, they still had to get past the Israeli Defence Forces, IDF, who control one of the best defined and electronically controlled borders in the world.”

The second incident referred to what was virtually a suicide mission by a Palestinian hang-glider.

The general’s statement is an impassioned reaction to the worldwide Israeli propaganda machine which seeks to downgrade the effectiveness of the UN’s peacekeeping force – mainly in the US media, but also in Britain and other countries of the EEC.

Final date

The proposed withdrawal policy being mooted by Israel must be seen for what it is – ”redeployment, nothing else”, says the general. The Nacquora agreement broke down in December because the Israelis refused to give the Lebanese a final date for the removal of all their troops from Lebanese soil. They withdrew the troops from Sidan on February 18th. This was to be “phase one” of a three-stage movement back to Israel. Since then, neither Lebanon or UNIFIL has been made aware of an overt intention to withdraw.

Callaghan is all too aware of the growing intimidation now being used by the Israelis, which has given rise to such frenetic activity involving Irish companies recently. The Beirut media are saying that Israel is trying to force UNIFIL to relinquish its operational areas south of the Litani river – inside a projected security zone which the Israelis are setting up within Lebanon to protect their northern border from attack, after the ultimate withdrawal of their forces.

The Israelis have made no secret of their desire to get the international peacekeeping soldiers on the move northwards to give Israel and its Lebanese collaborators a free hand in the security zone.

The general well knows the effect that such proposals could have on opinion in Ireland. But this is a soldier’s mission, he says, not a civilian’s, as he pays full tribute to maturity and common-sense of the private at his observation post who must assess risk every day and make the right decision. “It’s important that people at home should understand this,” he adds.

“The achievements and performance of Irish soldiers in the Lebanon have been truly phenomenal and it is internationally recognised after two decades of peacekeeping around the globe that they are among the most experienced in the world. The Lebanon is a great training ground for our men.

“In 1978, when UNFIL came, there were only 10,000 people living in this part of southern Lebanon, as a result of the sustained Israeli campaign against the PLO. Four years later there were 240,000 people living here, because of the UNIFIL presence. After the 1982 invasion a further 150,000 came into the UNIFIL zone: schools are opening and, believe it or not, housebuilding and construction is going on at an unprecedented rate. The local people, through their muktahs, and the Lebanese Government, want us to stay.”

He hands me a photocopy of the “US Congressional Record”, which contains ext racts from a speech by his friend, Peter Urquhart. Paraphrasing Benjamin Franklin, it says: “The blessing promised to peace makers, I fancy, relates to the next world, for in this they seem to have a greater chance of being cursed.”

We get up to shake hands. “You should root out the piece the Cruiser did in the Jerusalem Post,” he says, and winks.

IRISH STAND FIRM IN LEBANON QUICKSAND

Colman Cassidy files his frontline report

The checkpoint at Bra’shit, manned by the Irish, looked the LAUI (Lebanese armed and uniformed by the Israelis) straight in the eye.

From the LAUI checkpoint 100 metres away, Josef Almez drove towards the Irish. Almez was a LAUI belonging to a group of local mercenaries, highly volatile, that survive under Israeli patronage. Their checkpoints help to concentrate the minds of peacekeepers since they are at all times potential flashpoints.

Almez refused to submit his shiny BMW to the ignominy of a search. Such a stance by the LAUI is an everyday experience and is regarded as a routine occupational hazard. While they enjoy the favour of the occupying Israeli Defence Forces, IDF, they are kept in line effectively by UNIFIL, which tends to surround their checkpoints with strategically placed observation posts. The net result is that the LAUI cannot pass through a UNIFIL checkpoint, such as the one at Bra’shit, if they are either armed or in full uniform.

The Irish wanted to search Almez’s car, just in case. Nothing doing. He sped back to the LAUI checkpoint like a chicken without a head. The time was 17.05.

At 17.09, according to “B” Company’s commanding officer, Cammandant Padraig O’Callaghan, the LAUI, under a formidable local henchman of the Israelis, Abdul Nabbi, opened fire with a light machine gun. More fire came from a number of houses on the LAUI side of the village in support.

The Irish replied in kind, firing over the heads of their attackers. Eventually, the LAUI loosed off a rocket, which landed just beyond the Irish checkpoint, partially damaging the building that acts as platoon HQ. A second rocket followed which cleared the top of the building.

The situation was tense. The normal procedure in such incidents is for UNIFIL to contact the IDF. This was done by radio at local level, while at the same time, attempts were made to contact a senior IDF liaison officer, which would normally have the effect of bringing the Lauis to heel. To be fair, says O’Callaghan, there was a local response from the IDF two hours after the shooting commenced – at 19.15 – but it was not until late the following afternoon that they heard from the effective LAUI handler, the liaison officer. The local IDF had reported to the Irish that they’d ordered Nabbi to stop. The second rocket landed after that message had been received.

The situation was tense. The normal procedure in such incidents is for UNIFIL to contact the IDF. This was done by radio at local level, while at the same time, attempts were made to contact a senior IDF liaison officer, which would normally have the effect of bringing the Lauis to heel. To be fair, says O’Callaghan, there was a local response from the IDF two hours after the shooting commenced – at 19.15 – but it was not until late the following afternoon that they heard from the effective LAUI handler, the liaison officer. The local IDF had reported to the Irish that they’d ordered Nabbi to stop. The second rocket landed after that message had been received.

The Irish soldiers manning the checkpoint were ordered to move back to shelter in the building behind them as night fell. At daybreak they would review the situation.

The following morning at 08.15 the second part of this bizarre saga commenced. The Irish soldiers heard the excited voices of children coming from the direction of the village school. “It was strange, eerie even,” says O’Callaghan, “since the children would not normally be let out until lunchtime, at 12.” Nabbi, the 28-year old son of a local “gombeen” shop-keeper – who is also something of a key figure locally – had persuaded the teacher in the school to allow the children to “attack” the Irish position. If not, he would burn down the school. The kids, no doubt delighted at their new-found status in the eyes of the local LAUI bigwigs, took to the task with a vengeance.

Platoon commander Pat Whelan pulled back his men immediately. There was no way the peacekeepers could afford to be wrong-footed on this one. They could not even fire a warning shot over the heads of the marauding children. They entered the building and waited for the kids to run out of eggs.

When I arrived the smell of eggs was still discernible, but morale at platoon position 617 Alpha was good. Soldiers carried sandbags into the building – known colloquially as the “Commandant’s House”, although he doesn’t live there any more – and piled them high on the open rooftop, which overlooks both checkpoints, just in case the situation should erupt again. Amazingly, no one was hurt in the incident.

Pockmarks on the wall both inside and outside, however, pointed to the intensity of the LAUI firepower. Three lockers in a billet with three beds bore testimony to the havoc caused by ricocheting machine gun fire. Anyone asleep in that room would have had a rude awakening.

In a confrontational sense, the Irish platoon, which has more than five months of peacekeeping in the Lebanon behind it, could hardly be considered “innocent as a dove”. Now, with only four weeks left to its tour of duty with “B” Company of the 56th Infantry Battalion, that experience has made it and, indeed, the entire Irish battalion serving here, “as weary as a serpent”. And that, perhaps, is as it should be, given its location in this troubled land of the Bible.

The third bizarre feature surrounding the story is the fact that Abdul Nabbi and the Irish platoon commander were nattering together about this and that, a day later. This is the way of things out here. In the midst of this civilised exchange, however, Nabbi’s personality changed almost mid-sentence, and he strutted off making threatening noises.

Nabbi is not significant in any global operational sense. He is typical of the type of “freeloader” drafted in to help the Israelis contain and perpetrate hostilities in the area. The LAUI are a potential threat, more because their unpredictability, than for their military prowess. In this they contrast sharply with the de facto forces, DFF, which are in effect, remnants of the old Haddad Brigade. Both groups are now regarded by UNIFIL as forming the bulk of the so-called Lebanese army, which the Israelis employ to good effect in their efforts to enforce the “Iron Fist” policy that has overtaken the region – ever since the breakdown of talks between Israel and Lebanon held at UNIFIL headquarters in Nacquora – a few kilometres inside the border – in December.

Among the main reasons why these talks broke down, it is believed, is the fact that the Israelis were unwilling to supply the Lebanese with precise dates of their proposed withdrawal programme. Cynical observers of Israeli methods here believe that this withdrawal scenario could be rapidly turning into a redeployment of IDF troops on the ground.

No one knows precisely what the Israelis have in mind. If there is a move afoot to force UNIFIL to move away from its operational areas – “Irishbatt” in the case of the Irish – south of the strategically important Litani river, as some sources believe, it is almost certain to meet with fierce resistance from the peacekeeping forces, mainly through intervention at the United Nations.

The danger is, however, that Israeli-backed Lebanese militiamen could be used to further destabilise UNIFIL positions as in the Bra’shit case. That might be easily achieved if, as seems possible, the “South Lebanese army” – not to be confused with the Lebanese Army controlled by Beirut – is not quickly contained by the IDF, in the event of flashpoints erupting.

Men on the ground in the Irish Battalion at UNIFIL headquarters and Nacquora and at “Irishbatt” in Tibnin, in the mountains – within sight of Bra’shit – are genuinely perturbed, less at the possibility of intensified action in the region than at the international highlighting of the incident and the effects, particularly on their families at home.

There is resentment, too, at what is seen as the “Jeremiah stance” adopted by Conor Cruise O’Brien. Seasoned warriors who served in the Congo when O’Brien was there say he shoud have known better – in reference to his statement recently that it might be time for Ireland to bring home the troops, because of a worsening situation.

They point to UNIFIL’s achievements with some pride. Even the Shi’ites, it seems, have given credit to UNIFIL. And UNIFIL’s senior Irish personnel make the point, forcefully, that but for the forces’ presence, an almost tenfold increase in population in the area of Lebanon controlled by UN mandate, could never have been achieved.

Peacekeeping in Lebanon is a painstaking business which requires quantum skills of a specialised nature. It is, perhaps, appropriately summed up in a quotation from Lebanon’s best-known poet, Kahlil Gibran, who wrote in Sand and Loam: “Once in every 100 years Jesus of Nazareth meets Jesus of the Christians in a garden among the hills of Lebanon and they talk long: each time Jesus of Nazareth goes away, saying to Jesus of the Christians, ‘My friend, I am afraid we shall never never agree’.”

PREVENTIVE SHOOTING IS A THREAT TO IRISH

I had travelled past the Irish UNIFIL post on Friday, just an hour before an Israeli patrol loosed off a hail of machine gun fire within feet of a young officer. The incident was widely reported on international television that evening.

I had met the officer, Captain David Collins (a former member of the Irish rowing team), the previous evening, as he and his commanding officer, Lieut. Col. Con Crean, showed me around some of the key flashpoints in the Irish Battalion’s area of operations.

The Israelis passed the incident off to a group of wide-eyed journalists (most of them Jewish-Americans) as “preventive shooting”. Some of the journalists thought the Israelis could have been showing off because of the intensity of the machinegun fire. It is more likely, however, to be part of an emerging Israeli strategy of making life as difficult as possible for the Irish.

The so-called preventive shooting policy is something that the Israelis have employed a lot recently and is thought by some observers to be useful more as a crutch for flagging morale than as an effective deterrent against Shi’ites.

The incident happened at Haris, between Tibnin village where the Israelis have an outpost just above the main Irish position, and Yatar junction where there is a checkpoint manned by the Lebanese Israeli-backed militia, the LAUI (Lebanese armed and uniformed by Israelis).

Yatar and the nearby village have had their share of incidents recently. Only two weeks ago a local member of the Israeli-bcked militia, Ali Kitel, shot a couple of machinegun rounds at a bunch of women working in a field. Four were badly injured and a 10-year old girl was shot in the head and killed instantly.

An Irish armoured patrol carrier crew managed to lift out four of the women, one of who was shot in the groin and the other three in the legs.

Meanwhile, locals in the village retaliated by firing on the women’s attackers and the Irish were caught in between. Corporal Vinnie Thompson of Cathal Bruga Barracks and Privates Corky Byrne and Gerry Hogan, managed to lift the women clear, despite great danger to themselves, and take them to an ambulance.

It could have been a very nasty incident, since as far as the local were concerned, the Irish UN troops seemed to be assaulting the Israeli-backed Lebanese. The prompt action by the Irish soldiers reassured them, however.